The $80 Million Ice Cream Empire That Started with a Flat Tyre

On Memorial Day weekend, 1934, Athanasios Karvelas watched his ice cream melt under the scorching New York sun. His truck sat immobilised with a flat tyre in a parking lot next to a pottery store in Hartsdale. He had $15 to his name, borrowed from his girlfriend Agnes Stewart. His entire inventory was liquefying by the minute.

He sprinted into the pottery shop and struck a deal. Could he hook into their electricity? Could he sell from their lot?

The potter agreed. Within 48 hours, Karvelas had sold every drop of his melting ice cream to passing vacationers. They loved it. The texture, soft and creamy rather than rock-hard, was something completely new. Two revelations hit him simultaneously: customers preferred this "soft" ice cream, and selling from a fixed location beat driving a battered truck through summer heat.

That flat tyre launched an $80 million empire.

The Greek Immigrant Who Invented Soft Serve

Athanasios Karvelas was born in Athens on 14 July 1906. When he was four, his parents joined the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Greeks fleeing poverty for American opportunity, settling in Connecticut in 1910. By his twenties, he'd anglicised his name to Tom Carvel and bounced through careers: Dixieland drummer, Studebaker test driver, various trades that never stuck.

At 26, doctors incorrectly diagnosed him with fatal tuberculosis. Carvel fled to Westchester, New York, chasing country air and a fresh start. That's when he borrowed Agnes's $15 and became an ice cream vendor.

The Memorial Day breakdown changed everything. In 1936, Carvel bought the pottery store outright and converted it into America's first roadside soft-serve ice cream stand. Traditional ice cream at the time was hard, served in pre-frozen blocks or hand-scooped from frozen tubs. Carvel's product used a secret pastry cream formula kept at very low temperatures without completely freezing. The texture was revolutionary.

But Carvel faced a critical problem. He had no machine capable of producing soft serve consistently.

Building the First Soft Serve Machine

Carvel spent three years experimenting. In 1939, he patented what he called a "no air pump" super-low-temperature ice cream machine. Unlike traditional freezers that required air pumps to maintain consistency, Carvel's design used precise temperature control to keep his formula at exactly the right softness. He'd invented the first purpose-built soft-serve ice cream machine.

Sales exploded. By 1947, Carvel had established himself as the nation's first retailer of soft serve and was selling his patented machines to other shops. Then he spotted a bigger opportunity.

The Franchising Breakthrough

Carvel realised he could sell more than machinery. He could sell his entire system: the formula, the equipment, the training, the brand name. For a flat fee plus a percentage of profits, Carvel would teach independent store owners every detail of the soft serve business and let them operate under the Carvel name.

Franchising was barely understood in 1947. A few companies like Howard Johnson's had experimented with it before World War II, but the model hadn't taken off yet. Carvel became one of the earliest franchise pioneers in American food service.

The numbers tell the story. By the early 1950s, Carvel had opened 25 franchise locations. By 1981, the empire had grown to 700 stores. At its peak, over 500 Carvel shops operated worldwide, generating millions in revenue.

The Marketing Maverick

Carvel didn't just innovate in product and business model. He revolutionised his own marketing in ways that foreshadowed modern brand strategy.

First, he introduced "Buy one, get one free" promotions to American retail. The concept seems obvious now, but in the 1940s it was novel. Carvel would slightly increase his base price, then offer a second ice cream "free." Customers felt they were getting exceptional value. Volume sales offset the apparent discount.

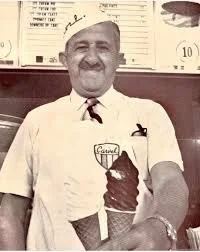

Second, he became one of the first company executives to star in his own television and radio commercials. His distinctive gravelly voice, white moustache, and unpretentious appearance made him a cult figure. He ran his own ads for decades.

"You can put a tall, handsome voice-maker with perfect voice, perfect pronunciation and perfect grammar," he told the New York Times in 1985. "But very few buyers of ice cream look like them. Our ads are aimed at people who look like us, talk like us and sound like us."

When asked why he chose to be the face of his company, his response was pure Carvel: "I couldn't find someone cheaper than me."

The strategy worked. Carvel's voice and face became synonymous with soft serve ice cream across America. His company introduced novelty ice cream cakes in shapes like "Fudgie the Whale" and "Cookie Puss" that became cultural touchstones, appearing in episodes of The Simpsons and Saturday Night Live sketches.

The Work Ethic That Built an Empire

Carvel's philosophy about work embodied the Greek immigrant drive that built his empire. When journalists asked about retirement, he bristled.

"Retirement? Why should I retire? I'm not working. You call this work? When you can get up seven days a week and do what you want to do and enjoy doing, that's not work. What's so pleasurable about watching TV shows and movies all day that show nothing but violence and car crashes? That's not the stuff that built this country."

He never retired. Carvel appeared in his own commercials and oversaw his empire until his death on 21 October 1990, at age 84. He left behind an estimated $80 million estate (which promptly descended into legal battles across New York, Florida, Delaware, and England), over 400 stores worldwide, and a franchising model taught in business schools.

More importantly, he left a product that changed global dessert culture.

The Bigger Implications

Carvel's story reveals three patterns that foreshadowed the modern food franchise explosion.

First, product innovation alone wasn't enough. Carvel invented both the machine and the formula, but the real breakthrough came from recognising that his expertise was more valuable than his hardware. He sold knowledge, not just equipment.

Second, personality-driven marketing decades before the age of founder brands. Carvel understood intuitively that authenticity mattered more than polish. His gravelly voice and working-class appearance built trust in ways that slick advertising couldn't replicate.

Third, franchising as a growth engine. Carvel spotted the power of the model in 1947, three years after Dairy Queen began franchising and five years before Ray Kroc turbo-charged McDonald's. While those brands grew larger, Carvel proved that even specialised products could scale through franchising.

Today, when you order soft serve at a beachside kiosk in Australia, a drive-through in Texas, or a gelateria in Italy, you're experiencing the ripple effects of that flat tyre in 1934. Carvel's accidental discovery became a global phenomenon. Soft serve is now a multibillion-dollar category, with chains like Dairy Queen operating over 7,000 locations worldwide.

The next time you're enjoying that smooth, creamy texture, remember Athanasios Karvelas from Athens. The Greek immigrant who watched his ice cream melt, recognised opportunity in disaster, and built an $80 million empire from a borrowed $15 and a parking lot next to a pottery store.

Sometimes the best innovations start with a flat tyre.